The researcher hoping to cure the world’s most common blood disorders

Sci-fi visions of the future often depict the perfect human: disease-free, ageless, and perhaps even immortal, with bionic bodies replacing the fragile vessels that we rely on today.

While this remains firmly in the realm of fiction for now, there’s one area of medical research that’s taking us places we could have never dreamed of mere decades ago – gene therapy.

With the chance of curing everything from hereditary blindness and cancer to fatal genetic disorders and Parkinson’s disease, it’s a field that has long excited Professor John Rasko AO, a haematologist who directs cell and molecular therapies at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (RPA) in Sydney.

Rasko is one of few medical researchers who can claim to have found a potential cure for a disease.

After leading an international genetic therapy trial for the blood disorder, thalassaemia, he reported in 2018 that, “We have cured the majority of the patients in the trial with transfusion-dependent beta thalassaemia.”

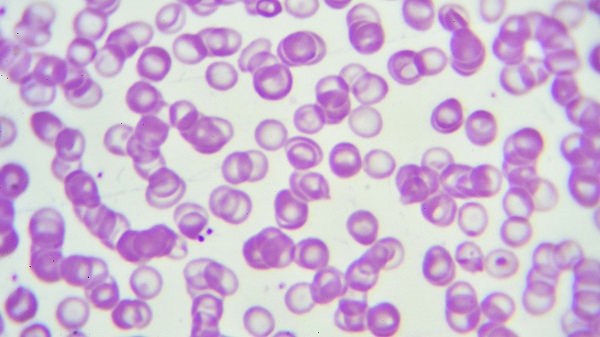

Thalassaemia is the world’s most common genetic disorder, affecting millions of people around the globe. It’s a life-threatening disease that sentences patients to a lifetime of transfusions, because their red blood cells don’t produce haemoglobin properly.

Working with an international team, Rasko’s therapy involved extracting stem cells that are the progenitors of red blood cells, inserting a healthy version of the faulty gene into them, and then intravenously infusing them back into the patients. The method cured 15 of the 22 thalassaemia patients involved in the trial.

Rasko, who also leads the Gene and Stem Cell Therapy Program at the University of Sydney’s Centenary Institute of Cancer Medicine and Cell Biology, says he’s excited about the possibilities of expanding that technology to a broader group of people with different diseases.

He’s already making strides in that direction, with equally promising results for another hereditary blood disorder, haemophilia. In people affected by that condition, blood doesn’t clot properly, so even a cut can be fatal if left untreated. These patients also require frequent transfusions of clotting factors.

Rasko’s method for treating patients with a version of the disorder called haemophilia B uses a harmless virus to carry a corrective gene into the liver. This allows them to produce coagulants normally.

“We inject the gene into their circulation, and it finds its way to their liver cells, where it takes up residence, hopefully permanently,” he says. “We’ve also seen cures in those patients.”

“We could potentially cure people with a single injection,” he adds. “I’ve often imagined a day when I could walk into a village in a far-off place and say to a person suffering from haemophilia, ‘In my back pocket, I’ve got some frozen virus. I’m going to inject it into your vein, and you won’t have any more bleeding ever again.’”

But between now and that exciting future lies a minefield of ethical and legal dilemmas.

“Gene therapy brings with it new moral responsibility and ethical requirements,” Rasko explains.

“We can imagine a future where we can remove disease-causing genes and let people enjoy a healthy life. But that brings up questions of how we see health and disease, and where we draw the line between treatment and disease eradication, versus enhancement.”

These ethical concerns are just one reason why this single injection to cure haemophilia is still decades away. Another reason for the slow progress is cost.

“Governments or industry have to pay for hundreds of millions of dollars of research and development over decades,” says Rasko.

As we venture into this brave new world of genetic modification, deeply informed and nuanced thinking around these issues is proving vital.

“Gene therapy raises a whole host of ethical, moral, and of course, practical, technical questions, as well as long-term safety questions that we really need to deal with,” says Rasko. “I have been humbled to discuss them in a series on radio and podcasts this year as the sixtieth Boyer Lecturer.”

“These are very complex questions that we’re dealing with, and they bring obligations that will require courage, imagination, and compassion at the highest level.”

It’s a challenge that hopefully our future selves will rise to meet.

By Hannah James

Updated 5 years ago