A new way to keep donated organs healthier in transit

Hundreds of Australians are lucky enough to receive life-changing surgery each year thanks to organ donation – but what happens if you don’t live close to your donor?

In 2018, some 1,782 people across the country received an organ transplant. But the waiting list is almost as long: around 1,400 people in Australia are currently in line for a donation.

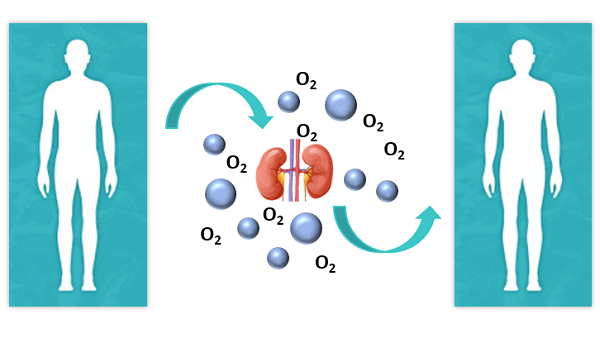

One problem with transplantation is that there are limits as to how long an organ can stay healthy outside of the human body before it starts to die. And if a donor and recipient are matched, but live in different parts of the country, shipping the potentially life-saving tissue from A to B is a significant challenge – even with the latest transportation techniques.

“Logistically, an organ transplant is a very long and complex process, especially if the donor and recipient are in different states,” chemical engineer Dr Negar Talaei says.

Enter OxyOcean: a product developed by Talaei that’s designed to keep donated organs alive for longer while in transit. The secret? A molecule found in crustaceans, dubbed OxyLone, that binds 40 times more oxygen than haemoglobin.

But helping organs on their journey to a recipient wasn’t always OxyOcean’s goal. Talaei initially set her sights on something smaller: transplanting human cells in a technique called “cell therapy”.

It was only when taking part in the 2019 NSW Medical Device Commercialisation Training Program– 12-week business-building courses and workshop series focussing on clinical trials, regulatory strategy and intellectual property – that Talaei started thinking bigger.

“Before the program, as a researcher, I didn’t take market size and clinical need into consideration. I knew they were important, but when you’re doing research, you’re thinking about other things like trying to support your hypothesis and publishing,” she says.

“That was one of the most valuable lessons that I learnt in the program: talking to people and trying to really understand their perspective on whether this technology would help them and if so, how it would.”

After discussions with stakeholders such as surgeons, physicians and donor coordinators, Talaei switched OxyOcean’s application to whole-organ transplantation, where she saw a bigger market and a greater clinical need than cell therapy.

Take, for instance, kidney transplants. They comprise more than half of all whole-organ transplants in Australia, and there’s a significant need for them: many of the nearly 13,400 people in Australia on dialysis would benefit from a kidney transplant.

While the OxyOcean technology is still in its early stages, Talaei plans to work with transplant surgeons in the next couple of years to show proof of concept in small mammals.

To do this, Talaei and her industry-based co-founder, who she also met through the program, are raising investment funding – something else she learnt to do in the program.

By shifting her focus from cell therapy to whole organ transplantation, Talaei recognises the value in embracing change.

“I remember in the first session of the program, the course director showed us a picture of a greyhound chasing a ball and he said, ‘In pursuing your business, you should be like this: fast, focused and agile’,” she says.

“That is one thing that I always have in my mind now – I need to be like that.”

By Bel Smith

Updated 5 years ago