New antibody blood test to reveal the state of our immunity

For a scientist drawn to the “endlessly fascinating” puzzle of getting to know a virus, 2020 has presented Dr Linda Hueston with unprecedented opportunity to focus on the highly infectious source of the COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2.

Just as the disease itself is still emerging, so too are effective weapons to arm the fight against it. And it’s for one of these, a potentially game-changing suite of information-rich blood tests, that Hueston has been awarded a NSW COVID-19 Research Grant.

Her innovative new ELISA (enzyme linked immunosorbent assay) test is set to tell a more detailed, accurate and nuanced story about COVID-19 immunity in individuals and, by extension, the population as a whole. Results could inform everything from individual diagnosis and treatment, and testing of vaccines, to more effective contact tracing, quarantine strategies and major government policy.

Chief serologist at the Institute of Clinical Pathology and Medical Research based at Westmead, Hueston joined Institute in 1979 and has vast experience investigating viral diseases including dengue fever and SARS-CoV-1. She developed the first diagnostic antibody tests in Australia for Zika virus, a mosquito-borne organism that, passed from mother to foetus, can cause devastating birth defects.

“A lot of the organisms I’ve worked with are problems for countries that are somewhat resource-poor, which produces added satisfaction that you were able to do something to help people who need help,” Hueston reflects. “The testing we’ve done has helped patients and clinicians, yet each test just started as an idea that just popped into a head and then turned into something real, that you can touch.”

Playing chess with COVID-19

Armed with a sample of SARS-CoV-2 early in the year, Hueston created a basic neutralisation test to establish the presence of total antibody: blood is mixed with live virus and applied to living cells, which die if virus is present. But that was the easy part. It soon became clear that, while readily grown in a lab, the new virus confounded some conventional wisdom, such as the usual sequence in which antibodies reveal themselves. “For me, it’s like a game: you and that organism have to find out about each other,” Hueston says. “I’ve found out a lot of things about this particular SARS organism that I’ve never seen in other viruses before.”

The neutralisation test results provided the scaffold on which to build three immunofluorescent antibody tests that allowed antibody class to be determined. PCR screening tests – the nasopharyngeal swabs performed by the millions – have been the major defence against COVID-19. But while effective in determining the presence of the virus at the time of testing, there are some questions PCR screening can’t answer that antibody tests can: Are antibodies present? Has the patient had the disease and, if so, when? And, if a vaccine becomes available, how effective is it?

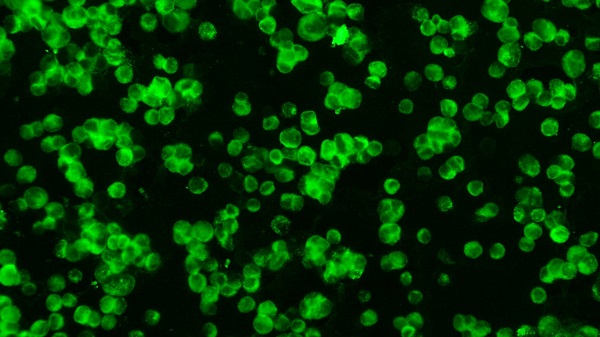

Antibody tests can help to answer these questions. Not only can they confirm PCR diagnosis, but also potentially paint a detailed picture of a patient’s interaction with the virus. Hueston has developed three blood tests using immunofluorescence – a technique that uses fluorescent dyes to identify antibodies associated with COVID-19 – which has been used for more than 30,000 tests since February. It was soon evident, though, that many more samples would need to be tested.

Her next move in the chess game against COVID is to design an ELISA test, sensitive enough to screen for three different types of antibody associated with COVID-19 at once. In an Australian-first, it will look for the antibodies IgG, IgA and IgM as well as total antibody. Together, this will provide unprecedented detail about a patient’s immunity.

“It means we can get results faster and that can help inform [a] government’s decision-making about things like how successful vaccines have been, and whether PCR results were correct or not; it can help us with timing of infection,” she explains.

The ELISA test needs lower level biosecurity containment and can be automated to screen samples night and day. This means fast, accurate results at reduced costs, which could play a vital part in solving the COVID-19 puzzle.

“Every day we learn something different about this virus, so it’s a matter of staying open and flexible to that,” Hueston explains. “And every patient adds a different layer. We all have immune systems with lots of things in common, but they’re also unique to each individual. You have to take into account all those little variables that add subtle colour. It’s not black and white; with this virus, you’re looking at the shade of grey.”

By Michelle Schlechta

Updated 4 years ago