Welcome to the largest biobank in the Southern Hemisphere

In 10 or 15 years, a frozen drop of your saliva or a piece of tumour could be the key to discovering new cures and treatments for a whole host of conditions.

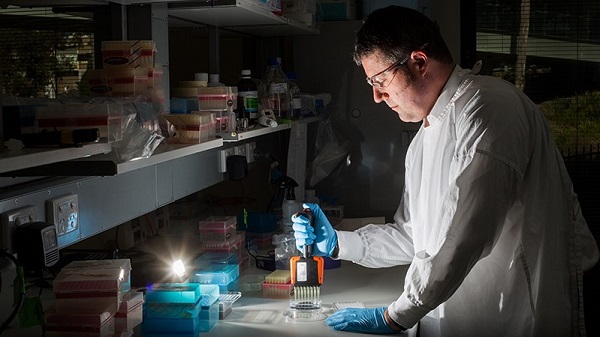

Associate Professor Craig Gedye, Clinical Research Director of the $12 million NSW Health Statewide Biobank in Camperdown, gets animated as he talks about the possibilities.

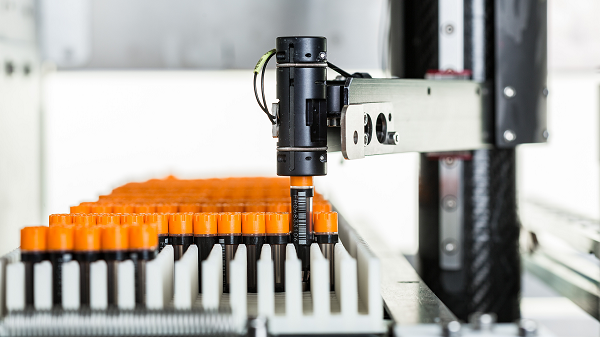

Armed with robotics that swing samples of blood, saliva, and tissue in and out of a series of freezers with temperatures as low as –196°C, the facility has the potential to store more than 3 million human biospecimens for ethically approved health and medical research.

“Let’s say you choose to donate a blood sample to a biobank after receiving a new form of cancer treatment, and then 10 years later we find out that you were in a car accident and you healed really slowly, or alternatively, you healed really rapidly,” says Gedye.

“Maybe there’s something special about you that means you heal really quickly. Or maybe your treatment in the past helped. By going back to your original sample, we can help understand what’s going on, and use that knowledge to help other people in the future.”

“We are going to be able to link your samples to create an overall health story and better understand it.”

The idea of a biobank isn’t new – biobanks exist all over the world, and are growing in importance due to advances in science, medicine, and technology. They are essential for translating research into real improvements in patient care and treatment.

There are more than 67 smaller facilities for preserving biospecimens in NSW alone, but the NSW Health Statewide Biobank at the Professor Marie Bashir Centre in Sydney is the largest in the Southern Hemisphere.

It has the ability to bring together a vast library of human biospecimens, providing clinicians and researchers with a huge resource of accessible material.

Making samples count

Biobanks are very expensive to set up and maintain; one freezer alone can cost around $20,000. Gedye says the Statewide Biobank will make a larger number of specimens available to a lot more approved researchers, taking away the financial pressure for individuals or institutions.

“NSW has made a very strategic investment here by creating a state-of-the-art repository that researchers worldwide will be able to access, for use in ethically approved studies,” says Gedye.

Many researchers accessing the Statewide Biobank are studying cancers, but others will be looking at conditions such as diabetes, arthritis, and dementia, as well as general population health.

Gedye’s own research is on the complexities of cancer.

“Between different patients, cancers that come from the same organ can behave completely differently, and treatments that help one patient fail the next. Why is this?” he asks.

“Why does a cancer lie dormant, then come back? Why does treatment not work in some patients, or work for a time, then fail?”

A few years ago, Gedye accessed an overseas biobank to study 430 tumours that had been removed from cancer patients – material that would usually be discarded.

“This is a terrible waste; any of these people’s cancers might teach us about that kind of cancer and the best treatment,” he says.

“The Statewide Biobank is an incredible resource. I might look after 30 people over the next two years with a particular medical problem, but if I can collaborate with others who are collecting specimens, then we suddenly have a wealth of information.”

Although the Statewide Biobank is housed in a medical research hub in Sydney, Gedye says samples can be collected at hundreds of locations around NSW, such as public hospitals, clinics, pathology collection centres, and operating theatres – wherever you traditionally get samples, such as blood, taken.

“People can participate in research wherever they are in the State,” he says.

Patients into superheroes

Samples will generally come into the Statewide Biobank from three sources: clinical trials testing new innovations in healthcare; specific disease collections that are relevant to NSW patients; or long-term community health surveillance projects.

Two high-profile examples of these longer-term projects are the 45 and Up study, looking at the health of middle-aged and older people in NSW, and the BABY1000 study focusing on the first three years of a baby’s life.

Participants in such projects will be asked if they are happy for samples to be preserved at the Statewide Biobank for the foreseeable future, and linked to information held in their NSW Health medical record.

“That decision to say ‘yes’ can result in all sorts of incredible benefits down the track,” says Gedye.

Some specimens stored in wax will

be preserved for decades, and others in deep freeze can be kept indefinitely.

Donor privacy is assured, with

identifying information separated from the sample, although if something

critical was discovered about a particular sample, such as risk for a serious health condition, the patient

would be contacted by a doctor or health professional.

“You have to spend a lot of time

collecting data originally. We want to be able to link people’s samples with

what happens to them,” says Gedye.

“What happened when they went to

hospital? What medicines did they use? Did it work? We can turn people into

superheroes; their identity may never been known, but their small action, their

donation and their ongoing story, becomes part of the research that helps us

solve big problems.”

Specimens in the Statewide Biobank are expected to help researchers understand everything from childhood cancers to dementia, as they reveal more and more about how an individual’s genes or other factors might affect their health.

“The next step is a functional

analysis of samples,” says Gedye. “We can effectively study people’s tissues or

tumours and say, ‘Your cancer was killed by this drug in a laboratory,’ before

we even give the drug to the patient.”

“In medicine, when a new

treatment comes along, there’s often a lot of enthusiasm for it, but once it’s made

available to patients, there’s often not enough monitoring of its effects,” he

adds. “We’re a very cheap and effective way of collecting samples to monitor

that.”

Gedye explains that people who have rare conditions often feel very frustrated that research is so slow, or that more isn’t being done to find a cure. The Statewide Biobank has great potential to provide solutions.

“We’re excited about our future

and the great potential that the Statewide Biobank has to support the people of

NSW. One day soon, we hope to invite the community to speak with their doctor

and proactively donate,” says Gedye.

“It’s incredible to think that

patients with a particular or rare medical condition would have an opportunity

to come to us and say, ‘We want you to look into our health condition. Here are

our samples.’ That’s the sort of relationship we aim to one day have with the

people of NSW.”

by Ken Eastwood

Updated 2 months ago